James Webb Space Telescope opens new window into hidden world of dark matter

The top image shows two galaxies from the JWST JADES survey seen in the first 1.8 billion years after the Big Bang. The bottom image shows a wave dark matter (PsiDM) simulation by the Pozo et al. team that illustrates the underlying smooth filamentary structure in the cosmic webb that utra-light dark matter particles would sustain, leading to star formation eventually happening in the densest dark matter regions, which also accumulate the hydrogen gas out of which these stars form.

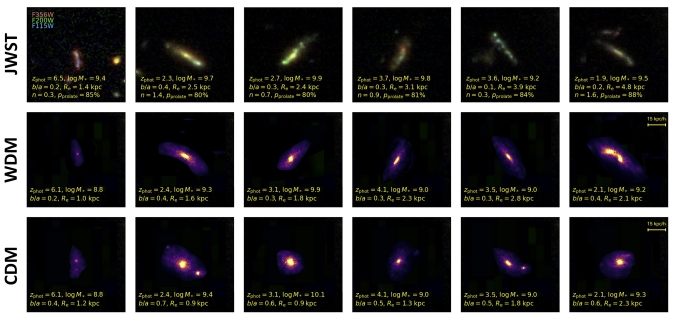

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed unparalleled details about the early universe: observations of young galaxies with unexpectedly elongated shapes that challenge established cosmological models.

This discovery represents a massive leap toward a new understanding on the nature of dark matter — the invisible substance that makes up the universe’s mass. By analyzing cold, warm and wave dark matter models through state-of-the-art simulations, JWST is transforming perceptions of the early cosmos.

The recent observations revealed many never-before-seen young galaxies that formed less than a billion years after the big bang. These galaxies appear strikingly elongated, unlike the familiar disk and spheroidal galaxies seen nearby today.

A new paper — published in Nature Astronomy — describing how these peculiar forms may hold vital clues to the true nature of dark matter was led by Álvaro Pozo of the Donostia International Physics Center and included Arizona State University co-author Rogier Windhorst.

“In the expanding universe defined by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, galaxies grow over time from small clumps of dark matter that form the first star clusters and assemble into larger galaxies via their collective gravity,” said Windhorst, a Regents Professor in ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and an interdisciplinary scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope.

“But now Webb suggests that the earliest galaxies may be embedded in marked filamentary structures, which — unlike cold, dark matter — smoothly join the star-forming regions together, more akin to what is expected if dark matter is an ultralight particle that also shows quantum behavior.”

To understand the origin of these unusual shapes means running simulations that show how the first galaxies formed in the early universe. Until now, astronomers have generally agreed that the earliest stars and galaxies formed when cool, pristine gas collected along a web of dark matter filaments. However, even the most advanced simulations based on the standard cold, dark matter model have struggled to reproduce the substantial elongation observed in the latest JWST images.

To investigate further, the study compares simulations that use alternative forms of dark matter: warm and wave dark matter, based on ideas involving sterile neutrinos and light axions from string theory. Wave dark matter simulations are particularly demanding because they require extremely fine resolution to capture tiny wave-like patterns while also modeling gas behavior.

“If ultralight axion particles make up the dark matter, their quantum wave-like behavior would prevent physical scales smaller than a few light-years to form for a while, contributing to the smooth filamentary behavior that JWST now sees at very large distances,” Pozo said.

The research team, which included experts from MIT, Harvard and Taipei, concluded that elongated young galaxies are abundantly produced in both the warm and wave dark matter scenarios, due to the smoother structure of cosmic filaments in these cases. Gas and stars flow steadily along such filaments, giving rise to prolate, elongated galaxy shapes.

This comparison can be further tested with future JWST observations, including spectroscopy, and with larger simulation volumes, potentially leading to decisive new insights into the still-unknown nature of the dark matter that dominates the universe.

This release was written by the Donostia International Physics Center press team with contributions from Kim Baptista of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

In memory of George F. Smoot

The research team dedicates this work to friend and mentor George Smoot, whose invaluable wisdom significantly contributed to this collaborative paper and will leave a lasting impact. He passed away shortly after the paper was accepted.

In connection with the new research, the team would like to highlight that Smoot was among the first to take the light axion interpretation seriously. More broadly, he inspired all of his colleagues through the breadth and depth of his understanding and his unwavering pursuit of fundamental questions across the entire field. This commitment is evident in his ongoing development of quantum detectors for astronomy, as well as his theoretical applications of general relativity to interpret gravitational wave events and understand the nature of dark matter.

More Science and technology

How AI is changing college

Artificial intelligence is the “great equalizer,” in the words of ASU President Michael Crow.It’s compelled industries, including higher education, to adapt quickly to keep pace with its rapid…

The Dreamscape effect

Written by Bret HovellSeventh grader Samuel Granado is a well-spoken and bright student at Villa de Paz Elementary School in Phoenix. But he starts out cautiously when he describes a new virtual…

Research expenditures ranking underscores ASU’s dramatic growth in high-impact science

Arizona State University has surpassed $1 billion in annual research funding for the first time, placing the university among the top 4% of research institutions nationwide, according to the latest…